Sam Ramsden in Conversation

Neil Tomkins in Studio shot by Hellene Algie

Neil Tomkins, in paint-stained flared Levi’s, a suit vest and green felt fedora, meets me at the entrance to his second-floor walk-up studio on Parramatta Road. The studio is shared by six artists, each with their own section. A communal whit-cube-like space serves as a mock gallery, where artists photograph and display their work to get a feel for it. Here hang the first complete and framed works for This Dream Called Reality. Despite being deeply familiar with Tomkins’ work, I am still surprised by the subtle leaps he takes between shows. In this case, the scale helps. The works are almost all large, cinemascopic landscapes, fragmented in ways we haven’t seen from the artist until recently. The shape lends itself beautifully to his new direction, leaving space for each individual puzzle piece to breathe, while interlocking to concisely form the single image. To Tomkins, there is “no difference between connection and separation.”

As he leads me to his corner, we pass another artist’s space, temporarily occupied by Tomkins work. Here, against the walls, lean the works one step away from being hung in the gallery section. In his own studio space, are hung two works in progress. His space is the definition of organised chaos, each wall with its own purpose, though only two are painting stations. The back wall houses the main work in progress, the true focus. On the right-hand wall hangs a work that is almost done, though not quite. Tomkins points to it, “I don’t know what this one needs.” It is a complex painting, with double-decker horizons pieced together from at least four source images. Prominent are two trees: one is silhouetted against a sharp mustard yellow in the foreground of the top image; the other is more realised in the middle-ground of the bottom. Both are set against dramatic, but wholly different skies. Lined up alongside the bottom tree like a grand still life: a traffic sign and powerline poles, each with its own cutting shadow. These lines dictate the structure of the work. Because of the fundamental instability of his unlikely landscapes, Tomkins has mastered anchoring his images with bold marks that hold together a painting’s structure, always on the verge of drifting and bleeding from the canvas. “It’s nice not having the pressure of being a realist.”

Sunset Tree 2019. Acrylic on Canvas

140cm 140cm

Until it is framed, each painting is at risk of complete alteration. The day before my visit, Tomkins was putting the final touches on a mammoth work. His progress must have halted, because on a whim he whipped the painting around, hanging it on its side. With a fresh palette, he went at the canvas, covering the surface almost completely. By the time of my visit, only a memory of the original image shimmers through the layered paint. As I leaf through a stack of the photo collages he puzzles together as jumping off points, Tomkins is adding to a brand-new composition. Dramatic skies – because these are often the lifeblood of his work – join at sharp angles. Dusk and dawn battle it out as the branches of a tree are pierced by rich purple sky. Later, he uses a charcoal to continue the outline of limb-like branches through the split, again anchoring a restless landscape. Tomkins later frames the paintings himself, a practice integral to his work over the last half-decade. The barely-treated timber frames serve almost as borders, containing the raw force of the painted surface.

A Space in Between 2019. Acrylic on Canvas

46cm x 36cm

We talk briefly about the collages that inform his painting. Tomkins has been described as a travel painter, and the countries that have been the sole inspiration for each of his previous exhibitions now fuse together. An Indian sky might meet a Portuguese road; an Australian road sign might yield a South American caravan. By cutting photos up and pasting them together, he gives us a glimpse into the combined memories that create his present point of view. We talk about archival tape, and search for information on his laptop as Son House’s blues plays in the background (“yesterday,” he says, “I listened to punk all day.”) Suddenly, his back to the double-decker painting an hour earlier proclaimed finished, he jumps up from his desk, dunks his long, weathered brush into black paint and viciously attacks a section featuring the shadow of a traffic sign. No work is safe until it hangs in the gallery, and even then it’s a toss-up.

It wouldn’t be a Neil Tomkins show without one or two works that take a marked step in the next direction. His process is one of discovery, largely because it is almost purely instinctive. Particles in Shifting Light is one of these works. In the foreground lurks a gum, its beautifully rendered bark textured and tactile, beseeching you to reach and peel it off the tree. The background, composed of two separate skylines, is bordered by a black plain, covering layers still felt in its surface. Purely abstract shapes dance free in this section of the painting. The work as a whole is clearly still rooted within the body of the show, but in the borders Tomkins creates room for himself to drive onward.

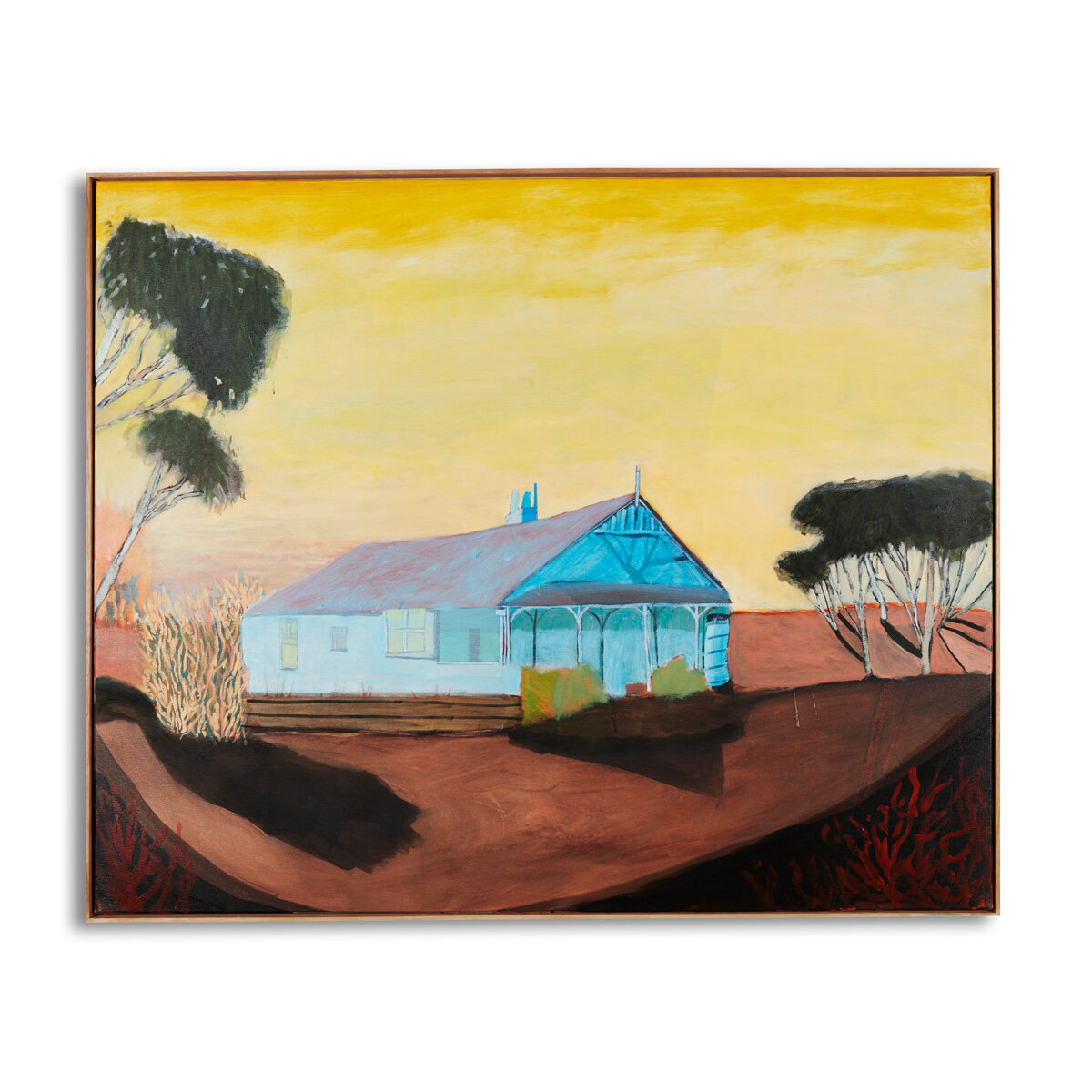

Blue Light House 2019. Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas

140cm x 171cm

This Dream Called Reality makes us believe Neil Tomkins when he tells us painting is his way of making sense of reality. His gestural strokes sharpen his vision. When he made the switch from oils to acrylic paint his practice became “more immediate.” When he added a new technique, in which he soaks a rag in water and black paint, rubbing it over the surface in wild movements, he was able to “give the surface an instant depth, knocking everything I painted back a bit.” As he simplifies and abstracts, pieces together scenes, Tomkins digs ever closer to a truth and purity of vision. This is how he sees, or at least close to it. He is opening the curtains for us to step into the world of a compulsive painter at the height of his game, with a truly unique vision.

Neil Tomkins in Studio shot by Hellene Algie